Printing the Declaration of Independence

Colonial printers held a rare position in the history of American printing. Printers in Great Britain had a legal monopoly on most printed material, such as the English-language Bible, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and all maps. American printers were limited to producing newspapers, almanacs, sermons, addresses, pamphlets, primers and other lesser items.

Most colonial printers had additional businesses. They ran book stores, dry-goods stores and some were postmasters as well. Printers were editors, publishers, and distributors who wore many hats. Colonial multi-taskers, so to say.

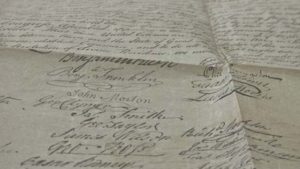

One of their crowning achievements was the nationwide distribution of the Declaration of Independence. Each of its printings has something important to tell us about life in the United States at the time of the birth of our republic.

Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence to be read by as wide an audience as possible. To this end, thirty newspapers in America printed it.

The Library of Congress owns fifteen original copies of these printings. Reading the Declaration as it first appeared in newspapers brings it to life as a living contemporary document that directed the course of history in the United States and throughout the world.

The promises to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness have yet to be achieved in much of the world. However, without these promises, we would not have come as far as we have today. Keeping the Declaration of Independence fresh and alive in our hearts and minds will continue the spread of democracy.

July 1776 was pivotal in the history of the United States and of democracy as well. The American Revolution was little more than a civil war. The Continental Army was outnumbered three to one by the British and their German mercenaries. The British Navy dominated the high seas, cutting off supplies and arms. America was seeking support both domestically and internationally. The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to draft a declaration of independence which would clearly state the reasons for the Revolution and acquire desperately needed arms, ammunition and soldiers. Thomas Jefferson wrote the original draft which was revised in committee and by the entire Congress. It was printed as a broadside on July 4 and distributed to be read publicly throughout the colonies. To achieve even wider distribution, Congress ordered it to be printed in newspapers as well.

July 1776 was pivotal in the history of the United States and of democracy as well. The American Revolution was little more than a civil war. The Continental Army was outnumbered three to one by the British and their German mercenaries. The British Navy dominated the high seas, cutting off supplies and arms. America was seeking support both domestically and internationally. The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to draft a declaration of independence which would clearly state the reasons for the Revolution and acquire desperately needed arms, ammunition and soldiers. Thomas Jefferson wrote the original draft which was revised in committee and by the entire Congress. It was printed as a broadside on July 4 and distributed to be read publicly throughout the colonies. To achieve even wider distribution, Congress ordered it to be printed in newspapers as well.

The Continental Congress saw the Declaration of Independence as an impressive instrument. The support of nations like France, the Netherlands, and Poland was crucial. Declaring independence made it possible to take the Revolution out of the arena of insurrection and put it directly on the international stage as a war for independence. The simplicity and eloquence of the Declaration of Independence immediately gained the attention of the world and has inspired democratic movements ever since. Getting the word out was a priority.

The Printers and their Newspapers

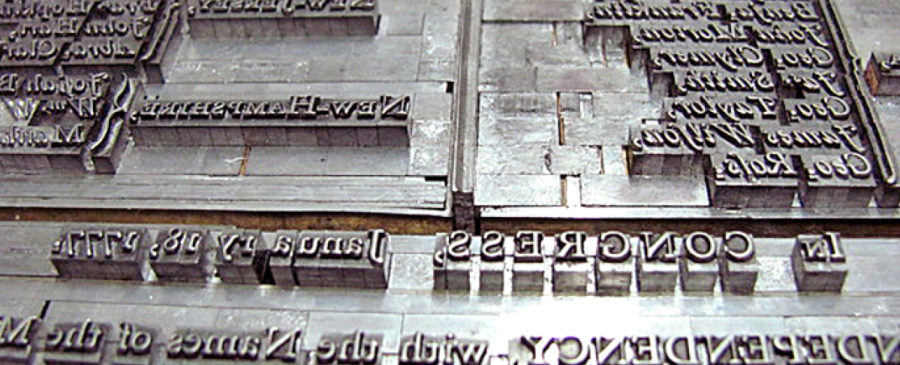

John Dunlap, a Philadelphia printer, took the manuscript copy of the Declaration and printed it as a single-sheet broadside on the evening of July 4, 1776. It took a little longer for it to appear in newspapers.

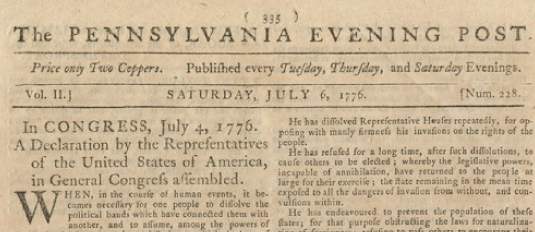

Benjamin Towne, a Philadelphia printer, was the first to print the Declaration in a newspaper. On Saturday, July 6, 1776, The Pennsylvania Evening Post, published every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, carried the Declaration of Independence on the front page.

Mary Katherine Goddard devoted the front page of her newspaper, The Maryland Journal and The Baltimore Journal, to the Declaration on Wednesday, July 10th. Mary Goddard was one of thirty female printers in the colonies. Printing was one the few professions open to women at this time. She was the first woman in the American colonies to serve as postmaster, a position she held for fourteen years.

July 6, 1776 — The Pennsylvania Evening Post featured the first full printing of the Declaration of Independence.

The Pennsylvania Gazette was the most successful newspaper in colonial America. It printed the Declaration of Independence on columns one and two on July 10, 1776. Benjamin Franklin, took control of this paper from Samuel Keimer in 1729, and then used his influence as postmaster to increase its circulation and list of subscribers. Franklin introduced the editorial column, humor, the first weather report and the first cartoon, the famous drawing of a divided snake with the caption "Join or Die" in 1754 in response to the French and Indian massacres of settlers in Virginia and Pennsylvania.

The Pennsylvania Journal was the major competitor to The Pennsylvania Gazette. On July 10, 1776, it printed the Declaration of Independence on page one. It was owned and run by William Bradford and his son Thomas. In 1754 he established the London Coffee-House, which served as the seat of the merchants' exchange in Philadelphia. The Bradfords were the official printers to the First Continental Congress. The Journal was a zealous advocate for the American Revolution.

On July 11th, a whole page of the Declaration of Independence was published, using a large font and embellishing it with a border of printers’ decorations, the most elaborate printing of a government document to date.

The New York Packet began publication in January 1776. The printer was Samuel Loudon, a young Irishman, who printed his newspaper on Thursday, so the earliest he could print the Declaration was on Thursday, July 11. The front page was devoted to a speech in the House of Lords by the Duke of Richmond. The Declaration does not appear until page two, column three.

This speech was a fierce debate in the House of Lords on the Revolution. The Duke of Richmond questioned the ability of the British to finance such a war and worried about the world's reaction to Great Britain destroying the farms, homes, and lives of colonials. He even mentioned the trial of Ethan Allen and described this patriot as the worst type of man, however useful in that he could be traded for British prisoners of war. This diatribe on the American Revolution precedes the Declaration of Independence. If anyone had any doubts about the need for independence, the Richmond speech quickly changed their minds. Reading the Declaration roused the reader to support and fight for freedom.

James Humphreys Jr. was a Tory who had taken an oath of allegiance to the King of England. His paper, The Pennsylvania Ledger, sported the King’s Arms in the masthead. He promised political impartiality in his byline. Benjamin Towne, the printer of The Pennsylvania Evening Post, badgered Humphreys for his political beliefs and drove him out of town in order to get a share of the congressional printings.

In an effort to appease his readers, Humphreys dropped the King’s Arms from his masthead on June 22nd. He published the Declaration of Independence on July 13 on page two. On the front page he printed a large ad for the second edition of Thomas Paine's seminal work Common Sense. Humphreys was a distributor for this work and used his newspaper to generate business for his book sales.

The Connecticut Courant, the oldest continuously printed newspaper in America, was established by Samuel Green, the descendant of a famous printing family in Connecticut. When Samuel died, his partner Ebenezer Watson took over the paper. After the British captured New York, The Connecticut Courant became the largest newspaper in the Northeast.

Ebenezer Watson was famous for his humanity and loyalty to independence. He discarded the King's Arms as the masthead and substituted the Arms of Connecticut. On July 15, 1776, he printed the Declaration of Independence on page two, following another report of speeches in the Parliament showing growing support for the American cause.

Watson died of smallpox in 1777. His wife, Hannah, took over the press. She was the first female printer in Connecticut and successfully ran the printing house through great adversity, including a disastrous fire that destroyed the Courant's paper mill. She petitioned the Connecticut Legislature for a loan to restore the mill. Within a day, the legislature approved a state-run lottery to support the rebuilding of the mill. The Courant didn't miss an issue.

Its printing of the Declaration after the pro-American speeches in Parliament shows another way printers could subtly shape support for independence, and its subsequent history confirms the importance of women printers in the Revolutionary era.

John Rogers began The American Gazette on June 22, 1776, but it only lasted a few weeks. This was enough time to include the Declaration of Independence in his July 16 issue. The Declaration is on the first page and the last page of the four pages of the paper. Inside was the Lord Richmond speech.

Thomas and Samuel Green were sons of the Samuel Green who established a printing dynasty in New England. These brothers published The Connecticut Journal between 1767 and 1809. They published the Declaration of Independence on July 17.

Edward Powars and Nathaniel Willis purchased The New England Chronicle from Samuel Hall on June 13, 1776. They ran the Declaration on the front page. Inoculation for smallpox was important in 1776, as its far safer and more effective modern form has become again today. The ad in The New England Chronicle illuminates one of the major dangers that threatened to undermine the American struggle for independence.

Isaiah Thomas founded The Essex Journal on December 4, 1773. Thomas was a prolific printer, editor, writer, and author of the definitive History of Printing in America. He also founded the American Antiquarian Society, the most important repository of eighteenth-century American newspapers in the world. Thomas sold his rights to the newspaper to Ezra Lunt in 1774 who then sold to John Mycall.

Mycall printed the Declaration on page one. Following the Declaration, there is a proclamation delivered on July 4 in Watertown, Massachusetts, calling for August 1 to be a day of "public humiliations, fasting and prayer," to bring an end to the British atrocities against Americans. The proclamation ends with the emphatic declamation "GOD save AMERICA!"

John Dixon and William Hunter printed the Declaration of Independence on page two of their July 20 issue of The Virginia Gazette out of Williamsburg, Virginia. Dixon and Hunter owned one of three newspapers titled "Virginia Gazette" in Williamsburg at this time. On June 1, 1776, they printed George Mason’s Declaration of Rights adopted by the Virginia constitutional convention.

Thomas Jefferson closely followed the wording and ideas of this document, as can be seen in its words "That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural rights, of which they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; among which are, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety."

Thomas Jefferson closely followed the wording and ideas of this document, as can be seen in its words "That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent natural rights, of which they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; among which are, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety."

The material the Gazette printed in the weeks surrounding the appearance of the Declaration of Independence supports Jefferson's contention that the Declaration was not an original work but "an expression of the American mind."

Benjamin Edes was a great patriot and printer in Boston. When the British took Boston he escaped by night in a boat with a press and a few types. He opened a printing house in Watertown, Massachusetts, where he continued publishing his paper The Boston Gazette. The quality of printing suffered greatly due to the deprivations of war. Printing presses, type, ink and paper were all imported from England. Edes had to work with worn type, poor quality ink, and a severe shortage of paper. The available paper was barely fit for printing.

To address the paper shortage, Edes advertised for rags from which paper was made. On the last column of page one, along with the Declaration of Independence, Edes advertised "Cash given for clean Cotton and Linen RAGS, at the Printing Office in Watertown." The Declaration appears here amid evidence of what the war for independence cost printers and their profession.

Alexander Purdie was born, and learned the printing trade, in Scotland. He printed the Declaration of Independence in his Virginia Gazette on the front page on July 26, 1776. At the top of column one he printed this notice: "In COUNCIL, July 20, 1776, Ordered THAT the printers publish in their respective Gazettes the DECLARATION of INDEPENDENCE made by the Honourable of the Continental Congress, and that the sheriff of each county of this commonwealth proclaim the same at the door of his courthouse the first court day after he shall have received the same." This notice is primary evidence of Congress's intent to use newspapers to print and disburse a government document.

Alexander Purdie was born, and learned the printing trade, in Scotland. He printed the Declaration of Independence in his Virginia Gazette on the front page on July 26, 1776. At the top of column one he printed this notice: "In COUNCIL, July 20, 1776, Ordered THAT the printers publish in their respective Gazettes the DECLARATION of INDEPENDENCE made by the Honourable of the Continental Congress, and that the sheriff of each county of this commonwealth proclaim the same at the door of his courthouse the first court day after he shall have received the same." This notice is primary evidence of Congress's intent to use newspapers to print and disburse a government document.

Purdie's patriotism is apparent in the newspaper masthead, where the Arms of Virginia include the famous phrase "Don't Tread on Me" and below the masthead is the subtitle "High Heaven to Gracious Ends directs the Storm!"

On page two following the Declaration is the following report: "Williamsburg, July 26. Yesterday afternoon, agreeable to an order of the Hon. Privy Council, the Declaration of Independence was solemnly proclaimed at the Capitol, the Courthouse, and the Palace amidst the acclamations of the people, accompanied by firing cannons and musketry, the several regiments of continental troops having been paraded on that solemnity." This is an eyewitness report of the celebrations surrounding the publication of the Declaration of Independence, a celebration that has continued uninterrupted for 240 years.

Congress wrote the Declaration of Independence to be read by as wide an audience as possible. To this end, thirty newspapers in America printed it. The Library of Congress owns fifteen original copies of these printings.

The promises to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness have yet to be achieved in much of the world, yet without these promises, we would not have come as far as we have today.

Keeping the Declaration of Independence fresh and alive in our hearts and minds will continue the spread of democracy. I hope that my sharing of the importance of studying the first printings of the Declaration of Independence in newspapers will educate and inspire you as much as it has inspired me.

For a detailed account please read this transcript by Robin Shields:

https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/journey/declaration-transcript.html

When I wrote 20/20: A Clear Vision for America, I described the issues that “We the People” are facing in 2016. We face the same concerns in 2016 that we faced in 1776. We are now facing tyranny from within. In 1776, about fifteen percent of Americans wanted sovereignty. I hope and pray that more citizens want it today. We must band together to agree on a new course. My book is clearly the solution Americans need.

God Bless us all and God Bless America. Our country, our Constitution, our culture, our civilization and our children need you now more than ever.

Don’t forget what these brave printers did for us.

Earlier articles related to 1776 Include:

Subscribe to Bill's monthly newsletter!

Please enter your name and e-mail below, and we will add you to our mailing list.

Finally, an author who brings you solutions, instead of problems.

Finally, an author who brings you solutions, instead of problems.

Americans have lost faith in their overreaching federal government. “We the People” don’t need to be overregulated or have their taxes misspent. Americans are victims of a crumbling economy, high prices and stagnant wages. They view government as bloated and politicians as corrupt.

They do not trust the leadership at any level. They see politicians of both parties as self-centered narcissists whose only objective is re-election. The author is like you, with one principal difference and 20 reasons for optimism. His “Vision” of America is “clear.” It is a vision of the Constitution and America the way it could be, the way it should be. The author’s eyesight is twenty-twenty.

Recent Comments